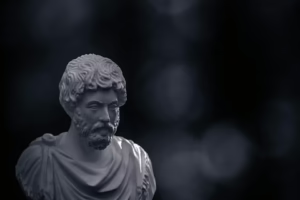

Plato vs. Socrates: Who Truly Defines the Good Life?

The inquiry into the Good Life has captivated philosophers since ancient times. Among the most influential figures in this discourse are Socrates and his student, Plato. Though their thoughts are inextricably linked, the nuances in their philosophies present a rich tapestry of ideas about virtue, knowledge, and the essence of happiness.

Socrates: The Philosopher of Virtue

Socrates, often hailed as the father of Western philosophy, espoused a dialectical approach to ethics known as the Socratic method. This technique involved asking probing questions to stimulate critical thinking and illuminate ideas. Socrates famously claimed that "the unexamined life is not worth living," emphasizing that self-reflection and the pursuit of virtue are paramount to a fulfilling existence.

For Socrates, the Good Life is closely aligned with the concept of virtue—specifically, the idea that knowledge is integral to virtuous action. He believed that no one willingly does wrong; when people act immorally, it is due to ignorance. Thus, acquiring knowledge and understanding the nature of good and evil are essential for achieving a good life. He argued that living virtuously leads to true happiness, asserting that the soul’s well-being is more important than physical pleasures or external success.

Socrates’ perspective on virtue is fundamentally tied to the idea that knowledge fosters ethical behavior. According to him, if individuals genuinely understand what is good, they will inevitably act accordingly. This concept underscores his belief in the transformative power of education and self-inquiry—a central tenet that resonates in modern philosophical discourse. Through conversations with others, Socrates sought to challenge assumptions, expose contradictions, and ultimately guide individuals toward a deeper understanding of their values.

To encapsulate Socratic thought, one might consider the relevance of his ideas in contemporary life. For example, self-examination remains a crucial part of personal development and ethical decision-making today. In a world inundated with information and noise, Socratic questioning can serve as a valuable tool for navigating moral complexities.

Plato: The Idealist

Plato, a student of Socrates, expanded upon his teacher’s ideas but also diverged significantly in his philosophical approach. In his works, especially the Republic, Plato presents a structured vision of justice and the Good Life, anchored in his Theory of Forms. Unlike Socrates, who emphasized empirical inquiry through dialogue, Plato posited the existence of abstract Forms or Ideas that represent the truest essence of concepts like Goodness and Justice.

For Plato, the Good Life is not merely about virtuous actions but an understanding of the Form of the Good. In his allegory of the cave, he illustrates the journey from ignorance to enlightenment, portraying the philosopher’s role as one who seeks to grasp the ultimate truths that govern reality. He depicts an ideal society, governed by philosopher-kings—wise individuals who comprehend the Good and strive to reflect it in governance. Plato asserts that the Good Life is achieved through a blend of knowledge, moral virtue, and societal structure, where individuals fulfill their roles within a just community.

One of the critical implications of Plato’s theory is the distinction between appearance and reality. While Socrates relies on dialogue to approach understanding, Plato elevates the significance of abstract reasoning. In The Republic, he envisions a society in which rulers, who have comprehended the Form of the Good, would guide citizens toward justice and virtue. Thus, Plato’s vision entails a more collective approach to the Good Life, where individual fulfillment is interwoven with societal harmony.

The implications of Plato’s philosophy extend beyond the individual into political theory. His ideas prompt reflection on how societies can cultivate environments conducive to the Good Life. This inquiry remains relevant today as we grapple with questions of governance, justice, and ethical leadership.

Divergent Paths: Knowledge and the Good Life

While both philosophers emphasize the importance of knowledge, their interpretations of its role differ significantly. Socrates directly connects the acquisition of knowledge with virtuous behavior, suggesting that learning leads to ethical living. His insistence on dialogue and self-examination as pathways to understanding signifies a more personal approach to the Good Life. Through his questions, Socrates invites individuals to confront their assumptions, fostering an environment where true knowledge can flourish.

Plato’s perspective, on the other hand, is systemic in nature. He posits that knowledge of the Good must transcend individual experience and be recognized as part of a larger, objective reality. In Platonism, understanding the Good involves grasping its universal essence and recognizing how it informs the ideal state of society. Thus, for Plato, the Good Life is a comprehensive state where individuals act in accordance with their understanding of the Good, ideally aligning with societal harmony.

This philosophical divergence raises essential questions about the nature of happiness and fulfillment. Is the Good Life an individual journey enriched by self-examination, as Socrates might argue, or is it a collective pursuit intimately tied to societal structure, as proposed by Plato? Each position offers unique insights but also invites critical examination of its limitations.

The Legacy of Their Philosophies

The debate between Socratic and Platonic views on the Good Life extends far beyond their eras. Socrates’ emphasis on dialogue and moral inquiry laid the groundwork for later existential and ethical thought, highlighting the importance of individual responsibility and authentic living. Ideas such as authenticity and the moral imperative to seek knowledge reflect Socratic influence on contemporary ethics.

Conversely, Plato’s idealism profoundly influenced political philosophy, particularly in discussions of justice and governance. His vision invites ongoing reflection on the interplay between individual fulfillment and societal structure. Concepts derived from his ideas, such as the role of the philosopher in politics and the significance of virtuous governance, continue to shape modern political discourse.

Moreover, the dialogue between their ideas endures in educational practices today. The Socratic method remains a hallmark of critical inquiry in educational settings, while Platonic ideals about knowledge and the ideal state provoke discussions regarding curriculum and civic education.

Conclusion: A Harmonious Debate

In the end, both Socrates and Plato offer valuable insights into the nature of the Good Life. Socrates champions individual virtue through self-examination, while Plato underscores the importance of understanding objective truths and their implications for society. Their philosophies invite us to engage in a continuous quest for knowledge and virtue—a journey that remains as relevant today as it was in ancient Athens.

Ultimately, the interplay of their ideas encourages us to ponder: Is the Good Life an individual pursuit defined by self-knowledge and virtue, or a collective ideal grounded in objective truths? The answer may lie in appreciating both perspectives and recognizing that the Good Life may be found at their intersection. By valuing both individual inquiry and the pursuit of universal truths, we can forge a more comprehensive understanding of what it means to live well.

In conclusion, the philosophical exploration of the Good Life remains a vital endeavor. In an age characterized by rapidly evolving societal norms and ethical dilemmas, Socrates and Plato continue to illuminate paths for reflection, dialogue, and personal growth. Their legacies compel us to engage with fundamental questions about virtue, knowledge, and the essence of happiness—challenges that, while ancient, are undeniably timely in our ongoing quest for a meaningful existence.

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?