Okay, buckle up. This is going to be a long and winding road through various philosophical terrains. I’ll aim for breadth rather than extreme depth in any single area, touching on key concepts, thinkers, and debates within general/broad philosophy topics. This article will cover a wide array of philosophical areas, including metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, political philosophy, aesthetics, and philosophy of mind.

A Whirlwind Tour Through the Landscape of Philosophy

Philosophy, at its core, is the systematic and critical examination of fundamental beliefs and assumptions about ourselves, the world, and our place within it. It’s a pursuit of understanding, driven by curiosity and a relentless questioning of the taken-for-granted. It’s a discipline that values reason and argumentation, seeking to construct coherent and justifiable answers to profound questions. Unlike many empirical sciences that rely primarily on observation and experiment, philosophy often delves into abstract concepts and thought experiments, relying on logical analysis and conceptual clarification.[modern_fn note=”Some branches of philosophy, such as experimental philosophy, do incorporate empirical methods to investigate philosophical questions.”]

I. Metaphysics: The Nature of Reality

Metaphysics, often described as “first philosophy,” is the branch of philosophy concerned with the fundamental nature of reality. It asks questions like: What is existence? What is time? What is space? What is causality? What are the fundamental constituents of the universe?

-

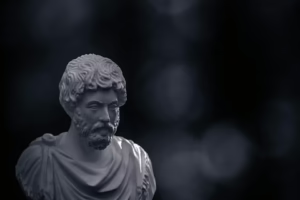

Being and Existence: A central question in metaphysics is the nature of being itself. What does it mean for something to exist? Different perspectives offer different answers. Plato, in his Theory of Forms, argued that true being resides in eternal and unchanging Forms, of which the physical world is merely a shadow.[modern_fn note=”Plato’s Theory of Forms is presented most prominently in his dialogues, particularly The Republic.”] Aristotle, while influenced by Plato, emphasized the importance of studying concrete, existing things in the world.[modern_fn note=”Aristotle’s metaphysical views are detailed in his Metaphysics.”] He developed a system of categories and principles to understand the structure and properties of substances. Existentialist philosophers like Jean-Paul Sartre and Martin Heidegger focused on the unique experience of human existence, emphasizing freedom, responsibility, and the encounter with nothingness.[modern_fn note=”Sartre’s Being and Nothingness and Heidegger’s Being and Time are foundational texts in existentialism.”]

-

Substance and Properties: Metaphysics also grapples with the relationship between substances (the things that exist) and their properties (the characteristics that those things possess). Are properties inherent in substances, or are they somehow separate? Substance dualism, famously advocated by René Descartes, posits that mind and body are distinct substances, each with its own essential properties.[modern_fn note=”Descartes’ dualism is articulated in his Meditations on First Philosophy.”] This view raises the problem of how these two distinct substances can interact. Materialism, on the other hand, asserts that everything that exists is ultimately material, and that mental properties are either identical to or emergent from physical processes.

-

Time and Space: The nature of time and space has been a subject of philosophical debate for centuries. Are time and space absolute and independent, as Isaac Newton believed, or are they relative and intertwined, as Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity suggests? Presentism claims that only the present exists, while eternalism holds that past, present, and future all exist equally.[modern_fn note=”McTaggart’s “The Unreality of Time” is a classic argument against the reality of time as a flow.”]

-

Causality: Causality, the relationship between cause and effect, is another fundamental metaphysical concept. How do we know that one event causes another? David Hume famously argued that we only observe constant conjunction between events, not a necessary connection.[modern_fn note=”Hume’s views on causality are presented in A Treatise of Human Nature and An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding.”] He questioned the justification for our belief in causal necessity. Different theories of causation attempt to explain the nature of the causal relation, including regularity theories, counterfactual theories, and causal process theories.

-

Free Will and Determinism: The debate over free will and determinism is a long-standing metaphysical problem. Determinism claims that all events are causally determined by prior events, leaving no room for free choice. Libertarianism asserts that we have genuine freedom to choose between different courses of action. Compatibilism (also known as soft determinism) attempts to reconcile free will and determinism, arguing that freedom is compatible with the existence of causal laws.

II. Epistemology: The Study of Knowledge

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature, scope, and limits of knowledge. It asks questions like: What is knowledge? How do we acquire knowledge? What are the sources of knowledge? How can we justify our beliefs?

-

What is Knowledge?: The traditional definition of knowledge is justified true belief. For a belief to count as knowledge, it must be true, you must believe it, and you must have adequate justification for believing it. However, this definition has been challenged by Gettier problems, which demonstrate that a justified true belief can still fail to be knowledge if the justification is based on luck or accident.[modern_fn note=”Edmund Gettier’s “Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?” is a seminal paper that sparked a revolution in epistemology.”]

-

Sources of Knowledge: Epistemologists identify various sources of knowledge. Empiricism claims that sensory experience is the primary source of knowledge.[modern_fn note=”John Locke’s An Essay Concerning Human Understanding is a cornerstone of empiricism.”] Rationalism, on the other hand, emphasizes the role of reason and innate ideas in acquiring knowledge.[modern_fn note=”Descartes’ rationalism is evident in his Meditations on First Philosophy.”] Testimony is another important source of knowledge, as we often rely on the reports and claims of others. Intuition is sometimes considered a source of knowledge, although its reliability is often questioned.

-

Justification: Justification is the process of providing reasons or evidence to support a belief. Different theories of justification include:

- Foundationalism: Claims that knowledge is built upon a foundation of basic, self-justifying beliefs.[modern_fn note=”Foundationalism is often associated with Descartes and his quest for certainty.”]

- Coherentism: Argues that a belief is justified if it coheres with a system of other beliefs.[modern_fn note=”Coherentism is often associated with thinkers like Otto Neurath and W.V.O. Quine.”]

- Externalism: Holds that justification can depend on factors external to a person’s conscious awareness, such as the reliability of the process that produced the belief.[modern_fn note=”Reliabilism, a form of externalism, is championed by Alvin Goldman.”]

-

Skepticism: Skepticism is the view that knowledge is impossible, or that we cannot be certain of our beliefs. Pyrrhonian skepticism aims to suspend judgment on all matters of belief. Cartesian skepticism, as exemplified by Descartes’ method of doubt, uses skeptical arguments to arrive at certain knowledge.[modern_fn note=”Descartes’ Meditations employs skeptical arguments to establish the foundations of knowledge.”]

-

Epistemic Virtues: Virtue epistemology focuses on the character traits and intellectual virtues that contribute to knowledge acquisition. Examples of epistemic virtues include open-mindedness, intellectual humility, intellectual courage, and carefulness.

III. Ethics: Moral Philosophy

Ethics, also known as moral philosophy, is the branch of philosophy that examines moral principles, values, and judgments. It explores questions about right and wrong, good and bad, duty and obligation.

-

Normative Ethics: Normative ethics seeks to establish moral standards and principles that guide our actions. Major approaches include:

- Consequentialism: Holds that the morality of an action is determined by its consequences. Utilitarianism, a prominent form of consequentialism, claims that we should strive to maximize overall happiness or well-being.[modern_fn note=”Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill are key figures in utilitarianism. Mill’s Utilitarianism is a classic text.”]

- Deontology: Emphasizes moral duties and rules, regardless of the consequences. Immanuel Kant’s categorical imperative is a central deontological principle, requiring us to act only according to maxims that we could will to become universal laws.[modern_fn note=”Kant’s ethical theory is developed in his Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals and Critique of Practical Reason.”]

- Virtue Ethics: Focuses on developing virtuous character traits, such as honesty, compassion, courage, and justice. Aristotle’s ethics emphasizes the importance of cultivating virtuous habits to achieve a flourishing life (eudaimonia).[modern_fn note=”Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics is a foundational text in virtue ethics.”]

-

Metaethics: Metaethics explores the meaning and nature of moral judgments. It asks questions like: Are moral statements objective or subjective? Are there moral facts? What is the relationship between morality and reason?

- Moral Realism: Claims that moral facts exist independently of our beliefs and opinions.[modern_fn note=”Moral realism has various forms, including ethical naturalism and ethical non-naturalism.”]

- Moral Anti-Realism: Denies the existence of objective moral facts. Forms of anti-realism include:

- Moral Subjectivism: Claims that moral judgments are expressions of personal feelings or opinions.

- Moral Relativism: Holds that moral standards are relative to cultures or individuals.

- Moral Error Theory: Argues that all moral statements are false because there are no moral facts to which they could correspond.

-

Applied Ethics: Applied ethics applies moral principles to specific practical issues. Examples include:

- Bioethics: Examines ethical issues in medicine and healthcare, such as abortion, euthanasia, and genetic engineering.

- Environmental Ethics: Addresses ethical issues related to the environment, such as climate change, pollution, and biodiversity loss.

- Business Ethics: Deals with ethical issues in business and commerce, such as corporate social responsibility, fair trade, and consumer protection.

IV. Political Philosophy: Justice, Power, and the State

Political philosophy examines the nature of the state, the justification of political power, the principles of justice, and the rights and responsibilities of citizens.

-

The State and its Justification: Political philosophers grapple with the question of why we need a state at all. Social contract theory, as developed by thinkers like Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, argues that the state is justified by the consent of the governed.[modern_fn note=”Hobbes’ Leviathan, Locke’s Two Treatises of Government, and Rousseau’s The Social Contract are classic texts in social contract theory.”] Individuals agree to surrender certain rights and freedoms to the state in exchange for protection and social order. Anarchism, on the other hand, rejects the legitimacy of the state and advocates for stateless societies based on voluntary cooperation.

-

Justice: Justice is a central concept in political philosophy. Different theories of justice offer different principles for distributing resources, opportunities, and burdens in society.

- Egalitarianism: Advocates for equality in the distribution of resources and opportunities.

- Libertarianism: Emphasizes individual liberty and limited government, arguing that individuals have a right to acquire and dispose of property as they see fit, as long as they do not violate the rights of others.

- Distributive Justice: Focuses on fair allocation of resources; theories differ on what constitutes fairness, ranging from equality to need-based distribution to meritocracy.

- Rawls’ Theory of Justice: John Rawls‘ theory of justice, presented in his book A Theory of Justice, argues for a “veil of ignorance” thought experiment, where individuals choose principles of justice without knowing their own position in society. Rawls argues that this would lead to the adoption of principles that protect the interests of the least advantaged.

-

Rights: Political philosophy is concerned with the nature and scope of rights. Natural rights are rights that are believed to be inherent in all human beings, regardless of law or custom. Legal rights are rights that are granted by law. Different theories of rights emphasize different values, such as liberty, equality, and security.

-

Democracy: Democracy, a system of government in which citizens have a voice in the decision-making process, is a major topic in political philosophy. Different models of democracy exist, including direct democracy, representative democracy, and deliberative democracy. Philosophical questions about democracy include: What are the conditions for a just and effective democracy? What are the limits of majority rule?

-

Power: The nature and exercise of power is another key concern of political philosophy. Philosophers analyze the different forms of power (e.g., coercive power, persuasive power, structural power) and the ways in which power is distributed and used in society. Thinkers like Michel Foucault have explored the relationship between power, knowledge, and discourse.[modern_fn note=”Foucault’s works, such as Discipline and Punish and The History of Sexuality, examine the interplay of power and knowledge.”]

V. Aesthetics: The Philosophy of Art and Beauty

Aesthetics is the branch of philosophy that explores the nature of art, beauty, and aesthetic experience. It asks questions like: What is art? What makes something beautiful? What is the value of art?

-

Defining Art: Defining art is a notoriously difficult task. Traditional definitions often focused on representation or beauty. However, modern art has challenged these definitions, with works that are abstract, conceptual, or even deliberately ugly. Institutional theories of art claim that something is art if it is recognized as such by the art world.[modern_fn note=”George Dickie’s institutional theory of art is a prominent example.”]

-

Beauty: Beauty is a central concept in aesthetics. Is beauty objective or subjective? Are there universal standards of beauty, or is beauty in the eye of the beholder? Different theories of beauty emphasize different qualities, such as harmony, proportion, and symmetry.

-

Aesthetic Experience: Aesthetic experience is the experience of appreciating art or beauty. It can involve a range of emotions, such as pleasure, awe, wonder, and even sadness. Philosophers have explored the nature of aesthetic experience, its relationship to knowledge and understanding, and its role in human flourishing.

-

The Value of Art: What is the value of art? Does art have intrinsic value, or is its value purely instrumental? Different theories emphasize different values of art, such as its ability to provide pleasure, to educate, to challenge our perspectives, to promote social change, and to express emotions.

-

Art and Morality: The relationship between art and morality has been a subject of debate for centuries. Should art be judged on moral grounds? Can art be immoral? Some argue that art has a responsibility to promote moral values, while others argue that art should be free from moral constraints. The debate over censorship in art often raises these issues.

VI. Philosophy of Mind: Exploring Consciousness and the Mental

Philosophy of mind explores the nature of the mind, consciousness, and mental states. It asks questions like: What is consciousness? What is the relationship between the mind and the body? Can machines think?

-

The Mind-Body Problem: The mind-body problem is the problem of explaining the relationship between mental states (such as thoughts, feelings, and sensations) and physical states (such as brain activity).

- Dualism: As mentioned earlier, dualism claims that mind and body are distinct substances. Substance dualism, as advocated by Descartes, posits that the mind is a non-physical substance that interacts with the physical body. Property dualism, on the other hand, claims that mental properties are distinct from physical properties, even if they are realized by physical systems.

- Materialism: Materialism claims that everything is ultimately material, and that mental states are either identical to or emergent from physical states. Different forms of materialism include:

- Identity Theory: Claims that mental states are identical to brain states.

- Functionalism: Defines mental states in terms of their causal roles, rather than their intrinsic properties. A mental state is identified by what it does, not by what it is made of.

- Eliminative Materialism: Argues that our common-sense understanding of the mind is fundamentally flawed, and that mental states as we typically conceive of them do not actually exist.

-

Consciousness: Consciousness, the subjective awareness of oneself and one’s surroundings, is a central topic in philosophy of mind. What is it like to be conscious? What are the necessary and sufficient conditions for consciousness? The “hard problem of consciousness,” as formulated by David Chalmers, is the problem of explaining how physical processes give rise to subjective experience.[modern_fn note=”Chalmers’ “Facing Up to the Problem of Consciousness” is a key paper in the debate about consciousness.”]

-

Artificial Intelligence (AI): The possibility of creating artificial intelligence raises profound philosophical questions. Can machines think? Could a machine be conscious? Alan Turing proposed the Turing test, a test of a machine’s ability to exhibit intelligent behavior indistinguishable from that of a human.[modern_fn note=”Turing’s “Computing Machinery and Intelligence” introduced the Turing Test.”] However, the philosophical implications of AI go far beyond the Turing test, raising questions about the nature of intelligence, consciousness, and personhood.

-

The Problem of Other Minds: The problem of other minds is the problem of knowing whether other beings have minds and conscious experiences like our own. We can observe the behavior of others, but we cannot directly access their subjective experiences. How can we justify our belief that other people are conscious?

VII. Logic: The Art of Reasoning

While logic underpins almost every area of philosophy, it also stands as its own substantial field. It’s the study of valid reasoning and argumentation. It provides the tools and frameworks for constructing sound arguments and identifying fallacies.

-

Propositional Logic: This branch deals with logical relationships between statements. Key concepts include:

- Connectives: Symbols like AND (&), OR (v), NOT (~), IF-THEN (->), and IF AND ONLY IF (<->) which link propositions.

- Truth Tables: Used to define the meaning of logical connectives and evaluate the truth value of complex statements.

- Validity and Soundness: A valid argument is one where the conclusion follows logically from the premises. A sound argument is one that is valid and has true premises.

-

Predicate Logic (First-Order Logic): Extends propositional logic to deal with quantifiers (e.g., “all”, “some”) and predicates (properties or relations). This allows for expressing more complex statements about objects and their attributes.

-

Modal Logic: Deals with modalities like possibility, necessity, belief, and knowledge. It introduces operators like “it is necessary that” and “it is possible that.”

-

Informal Logic: Focuses on the analysis and evaluation of arguments as they occur in everyday language. This involves identifying fallacies, biases, and other factors that can undermine the strength of an argument.

-

Fallacies: Common errors in reasoning that can make an argument invalid or unsound. Examples include:

- Ad Hominem: Attacking the person making the argument rather than the argument itself.

- Straw Man: Misrepresenting someone’s argument to make it easier to attack.

- Appeal to Authority: Claiming that something is true simply because an authority figure says so.

- False Dilemma: Presenting only two options when more exist.

- Begging the Question: Assuming the conclusion in the premises.

VIII. Philosophy of Language: Meaning, Reference, and Communication

Philosophy of language explores the nature of meaning, reference, truth, and communication. It asks questions like: What is meaning? How do words refer to things in the world? How do we understand each other?

-

Theories of Meaning: Several theories attempt to explain the nature of meaning:

- Reference Theory: Claims that the meaning of a word is the object or concept to which it refers.

- Ideational Theory: Holds that the meaning of a word is the mental image or idea it evokes.

- Use Theory: Argues that the meaning of a word is determined by how it is used in language. Ludwig Wittgenstein famously advocated for a use theory of meaning.[modern_fn note=”Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations is a highly influential work on the philosophy of language.”]

-

Reference: Reference is the relationship between words and the objects or concepts to which they refer. How do words “hook onto” the world?

-

Truth: Theories of truth attempt to define what it means for a statement to be true. Different theories include:

- Correspondence Theory: Claims that a statement is true if it corresponds to a fact.

- Coherence Theory: Argues that a statement is true if it coheres with a system of other beliefs.

- Pragmatic Theory: Holds that a statement is true if it is useful or practical to believe.

-

Speech Act Theory: Explores the different types of actions that we perform with language, such as making statements, asking questions, giving commands, and making promises. J.L. Austin and John Searle are key figures in speech act theory.[modern_fn note=”Austin’s How to Do Things With Words and Searle’s Speech Acts are foundational texts in speech act theory.”]

-

Meaning and Context: The meaning of a word or phrase can often depend on the context in which it is used. Pragmatics is the study of how context influences meaning.

IX. Philosophy of Science: Exploring the Nature of Scientific Knowledge

Philosophy of science examines the foundations, methods, and implications of science. It asks questions like: What is science? What is the scientific method? How do scientific theories explain the world?

-

The Scientific Method: The scientific method is a systematic approach to acquiring knowledge that involves observation, hypothesis formation, experimentation, and analysis. However, philosophers of science debate the precise nature of the scientific method and whether there is a single, unified method that applies to all sciences.

-

Scientific Realism vs. Anti-Realism:

- Scientific Realism: Claims that scientific theories aim to provide a true description of the world, and that successful theories are likely to be at least approximately true.

- Scientific Anti-Realism: Denies that scientific theories necessarily aim to provide a true description of the world. Different forms of anti-realism include:

- Instrumentalism: Claims that scientific theories are merely tools for making predictions, not necessarily true descriptions of reality.

- Constructivism: Argues that scientific knowledge is socially constructed, and that scientific theories reflect the values and interests of the scientists who create them.

-

Explanation: Philosophers of science are concerned with the nature of scientific explanation. What makes a good explanation? Different theories of explanation include:

- Deductive-Nomological (DN) Model: Claims that an explanation is a deductive argument that derives the explanandum (the thing to be explained) from the explanans (the explanatory premises), which must include at least one law of nature.

- Causal Explanation: Emphasizes the role of causal relationships in explaining phenomena.

-

Confirmation and Evidence: How do we confirm scientific theories? What counts as evidence for or against a theory? Karl Popper argued that scientific theories are falsifiable, meaning that they can be proven wrong by empirical evidence.[modern_fn note=”Popper’s The Logic of Scientific Discovery is a key text in the philosophy of science.”] He emphasized the importance of testing theories rigorously and attempting to falsify them.

-

Scientific Revolutions: Thomas Kuhn argued that scientific progress is not a linear accumulation of knowledge, but rather a series of revolutionary shifts in paradigms, or fundamental frameworks of thought.[modern_fn note=”Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions is a highly influential work on the history and philosophy of science.”]

X. Philosophy of Religion: Faith, Reason, and the Divine

Philosophy of religion explores fundamental questions about religion, faith, and the existence of God. It asks questions like: Does God exist? What is the nature of God? What is the relationship between faith and reason?

-

Arguments for the Existence of God: Philosophers have proposed various arguments for the existence of God, including:

- Ontological Argument: Attempts to prove God’s existence from the very concept of God. Anselm of Canterbury developed a famous ontological argument.[modern_fn note=”Anselm’s ontological argument is presented in his Proslogion.”]

- Cosmological Argument: Argues that the existence of the universe requires a first cause or uncaused cause, which is identified with God. Thomas Aquinas presented a version of the cosmological argument in his Summa Theologica.[modern_fn note=”Aquinas’ Summa Theologica provides a comprehensive overview of his philosophical and theological views.”]

- Teleological Argument (Argument from Design): Argues that the complexity and apparent design of the universe suggest the existence of an intelligent designer.

-

The Problem of Evil: The problem of evil is the problem of reconciling the existence of evil and suffering in the world with the existence of an all-powerful, all-knowing, and all-good God. Different responses to the problem of evil include:

- Theodicy: An attempt to justify God’s existence in the face of evil.

- Free Will Defense: Argues that God gave humans free will, and that evil is a consequence of human choices.

-

Faith and Reason: The relationship between faith and reason has been a central topic in philosophy of religion. Can faith be justified by reason? Is faith compatible with reason? Different perspectives include:

- Fideism: Claims that faith is independent of reason, and that religious beliefs should not be subject to rational scrutiny.

- Rationalism: Argues that religious beliefs should be based on reason and evidence.

-

Religious Language: What is the meaning of religious language? Do religious statements refer to objective realities, or are they merely expressions of personal feelings or beliefs?

-

The Nature of God: What is the nature of God? Is God personal or impersonal? Is God omnipotent, omniscient, and omnibenevolent? Different religions and philosophical traditions offer different conceptions of God.

XI. Existentialism: Freedom, Responsibility, and Meaning in a Meaningless World

Existentialism is a philosophical movement that emphasizes individual freedom, responsibility, and the search for meaning in a seemingly meaningless world.

-

Key Themes:

- Existence Precedes Essence: Humans are born into the world without a predetermined purpose or essence. We create our own essence through our choices and actions.

- Freedom and Responsibility: We are radically free to choose our own values and actions. This freedom comes with a profound responsibility for the consequences of our choices.

- Authenticity: We should strive to live authentically, in accordance with our own values and beliefs, rather than conforming to societal expectations.

- Angst (Anxiety): The awareness of our freedom and responsibility can lead to anxiety or dread.

- Absurdity: The world is inherently meaningless and irrational. We must confront this absurdity and create our own meaning.

-

Key Figures:

- Søren Kierkegaard: Often considered the father of existentialism. He emphasized the importance of individual faith and the leap of faith.

- Friedrich Nietzsche: Proclaimed the “death of God” and challenged traditional moral values.

- Jean-Paul Sartre: A prominent existentialist philosopher who emphasized freedom, responsibility, and the concept of “bad faith.”

- Albert Camus: Explored the themes of absurdity, rebellion, and the search for meaning in his novels and essays.

XII. Phenomenology: Describing Experience as It Is Lived

Phenomenology is a philosophical approach that focuses on the study of consciousness and experience from a first-person perspective. It seeks to describe phenomena as they are directly experienced, without imposing pre-conceived categories or theories.

-

Key Concepts:

- Intentionality: The directedness of consciousness towards objects or states of affairs. Consciousness is always “consciousness of” something.

- Epoche (Bracketing): The suspension of judgment about the existence or nature of the external world in order to focus on the pure experience.

- Lived Experience: The subjective, qualitative aspects of experience.

- Intersubjectivity: The relationship between consciousnesses, and the way in which we come to understand each other’s experiences.

-

Key Figures:

- Edmund Husserl: The founder of phenomenology. He sought to develop a rigorous science of consciousness.

- Martin Heidegger: Expanded upon Husserl’s phenomenology, focusing on the question of being and the nature of human existence.

- Maurice Merleau-Ponty: Explored the relationship between consciousness, the body, and the world.

XIII. Poststructuralism and Deconstruction: Challenging Structures and Meanings

Poststructuralism and deconstruction are philosophical approaches that challenge traditional ideas about structure, meaning, and truth. They argue that language is not a neutral medium for representing reality, but rather a system of signs that shapes our understanding of the world.

-

Key Concepts:

- Deconstruction: A method of analyzing texts that seeks to expose the inherent contradictions and instability of meaning.

- Différance: A term coined by Jacques Derrida to describe the way in which meaning is always deferred and dependent on difference.

- Logocentrism: The tendency to privilege certain concepts or ideas as central and authoritative.

- Power and Knowledge: Poststructuralists argue that power and knowledge are intertwined, and that knowledge is always shaped by power relations.

-

Key Figures:

- Ferdinand de Saussure: His structuralist linguistics laid the groundwork for poststructuralism.

- Jacques Derrida: A key figure in deconstruction.

- Michel Foucault: Explored the relationship between power, knowledge, and discourse.

- Julia Kristeva: Contributed to feminist theory and psychoanalysis.

XIV. Critical Theory: Examining Power Structures and Social Justice

Critical theory is a philosophical approach that seeks to critique and transform social structures that perpetuate inequality and oppression. It examines the ways in which power operates in society, and how dominant ideologies maintain social control.

-

Key Themes:

- Critique of Ideology: Critical theorists seek to expose the ways in which dominant ideologies distort reality and serve the interests of the powerful.

- Emancipation: The goal of critical theory is to promote human emancipation and social justice.

- Interdisciplinarity: Critical theory draws on insights from various disciplines, including philosophy, sociology, history, and political science.

-

Key Figures:

- The Frankfurt School: A group of influential critical theorists, including Max Horkheimer, Theodor W. Adorno, Herbert Marcuse, and Jürgen Habermas.

- Jürgen Habermas: Developed a theory of communicative rationality and argued for the importance of public discourse in a democratic society.

XV. Feminism: Gender, Power, and Equality

Feminist philosophy examines the ways in which gender shapes our understanding of the world, and the ways in which women have been historically marginalized and oppressed. It seeks to promote gender equality and social justice.

-

Key Themes:

- Critique of Patriarchy: Feminist philosophers critique patriarchal social structures and ideologies that perpetuate male dominance.

- Gender as a Social Construct: Feminists argue that gender is not simply a biological category, but rather a social construct that is shaped by culture and history.

- Intersectionality: The recognition that gender intersects with other social categories, such as race, class, and sexuality, to create unique experiences of oppression.

-

Different Strands of Feminism:

- Liberal Feminism: Emphasizes individual rights and equal opportunities for women.

- Radical Feminism: Critiques the entire patriarchal system and seeks to transform social structures.

- Socialist Feminism: Connects women’s oppression to the capitalist system.

- Poststructuralist Feminism: Draws on poststructuralist ideas to deconstruct gender categories and challenge essentialist views of women.

XVI. Environmental Philosophy: Ethics and Our Relationship with Nature

Environmental philosophy explores the ethical and philosophical implications of our relationship with the environment. It asks questions like: Do non-human animals have moral rights? What is our responsibility to future generations? How should we balance human needs with the preservation of nature?

-

Key Themes:

- Anthropocentrism vs. Non-Anthropocentrism: The debate over whether humans are the center of moral consideration (anthropocentrism) or whether non-human entities also have moral value (non-anthropocentrism).

- Intrinsic Value vs. Instrumental Value: Does nature have value in itself (intrinsic value), or is its value only derived from its usefulness to humans (instrumental value)?

- Sustainability: The concept of meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

-

Different Approaches:

- Deep Ecology: A radical environmental philosophy that emphasizes the interconnectedness of all living things and the need for a fundamental shift in human values.

- Ecocentrism: An ethical perspective that prioritizes the well-being of ecosystems over individual organisms.

- Environmental Justice: Focuses on the fair distribution of environmental benefits and burdens, and the ways in which environmental problems disproportionately affect marginalized communities.

XVII. Philosophy and Technology: The Ethical and Social Implications of Technological Advancements

Philosophy and technology examines the ethical, social, and philosophical implications of technological advancements. It asks questions like: What is the impact of technology on human life and society? How should we regulate technology? What are the risks and benefits of new technologies?

-

Key Themes:

- Technological Determinism vs. Social Construction of Technology: The debate over whether technology shapes society (technological determinism) or whether society shapes technology (social construction of technology).

- Privacy and Surveillance: The ethical implications of data collection and surveillance technologies.

- Artificial Intelligence and Automation: The potential impact of AI and automation on employment, inequality, and human autonomy.

- Bioethics and Technology: The ethical challenges posed by technologies such as genetic engineering, reproductive technologies, and life extension.

Conclusion: The Enduring Value of Philosophical Inquiry

This whirlwind tour has only scratched the surface of the vast and complex landscape of philosophy. We’ve touched on fundamental questions about reality, knowledge, morality, politics, art, mind, language, science, religion, existence, experience, structures, power, gender, environment, and technology. Each of these areas could be explored in much greater depth, and there are many other branches of philosophy that we haven’t even mentioned.

Despite its abstract nature, philosophy has profound practical implications. It helps us to clarify our values, to think critically about our beliefs, to make informed decisions, and to live more meaningful lives. In a world that is increasingly complex and rapidly changing, the skills and insights that philosophy provides are more valuable than ever. By engaging with philosophical questions, we can become more thoughtful, responsible, and engaged citizens of the world. The examined life, as Socrates said, is the only life worth living. And the tools of philosophy provide us with the means to conduct that examination with rigor and depth. The journey of philosophical inquiry is never truly finished; it is a continuous process of questioning, reflecting, and striving for a deeper understanding of ourselves and the world around us.

Add Comment