From Ancient Greece to Today: The Evolution of Meaning in Philosophy

Introduction

Philosophy, deriving from the ancient Greek word for “love of wisdom,” has undergone a profound transformation since its inception. The evolution of meaning within philosophical discourse reflects the shifting paradigms, cultural contexts, and intellectual landscapes of different eras. This article explores the journey of philosophical meaning from the classical period of Ancient Greece to contemporary thought, highlighting key figures and movements that have shaped our understanding of philosophy today.

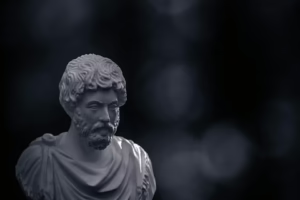

I. The Birth of Philosophy in Ancient Greece

A. The Presocratics

The journey can be traced back to the Presocratic philosophers (c. 600-400 BCE), who primarily focused on cosmology, metaphysics, and the nature of existence. Figures like Thales, Anaximander, and Heraclitus sought to explain the universe through rational thought rather than mythological narratives. Thales, regarded as the first philosopher, proposed that water was the fundamental principle (archê) of all things, while Heraclitus famously posited that change is the essence of the universe—“you cannot step into the same river twice.” These early inquiries set the foundation for philosophical thought, introducing the idea that reason could lead to understanding the cosmos.

B. Socratic Philosophy

The transition to Socratic philosophy marked a significant shift in focus from the external universe to the internal human experience. Socrates (c. 470-399 BCE) emphasized ethical inquiries, addressing the nature of virtue and the best way to live. His method of dialectical questioning, known as the Socratic method, encouraged critical thinking and self-examination. Socrates famously asserted that “the unexamined life is not worth living,” implying that the search for personal meaning and moral understanding is fundamental to human existence.

C. Platonic Ideals

Plato (c. 427-347 BCE) built on Socratic ideas, proposing that true knowledge transcends the physical world. In his allegory of the cave, he depicted individuals as prisoners who only perceive shadows of reality; true enlightenment occurs when one ascends out of the cave and perceives the Forms—ideal and unchangeable concepts that embody the essence of all things. Plato’s emphasis on abstract ideals created a metaphysical framework that would influence centuries of philosophical thought.

D. Aristotle’s Empiricism

Aristotle (384-322 BCE), Plato’s student, introduced a more empirical approach. He acknowledged the significance of sensory experience as a way to gain knowledge. His works on ethics, politics, and metaphysics explored virtue, the good life, and the nature of reality. Aristotle’s contributions to logic and scientific methodology laid the groundwork for future developments in philosophy, emphasizing the interrelation between theory and empirical observation.

II. The Hellenistic Period and the Expansion of Philosophical Thought

A. Stoicism and Epicureanism

Following the classical period, philosophy flourished in the Hellenistic world (c. 323-30 BCE). Stoicism, founded by Zeno of Citium, posited that virtue is the highest good and emphasized the importance of living in accordance with nature. Stoics believed in the rational order of the universe and advocated for emotional resilience through acceptance of fate. Epictetus and Seneca further developed Stoic thought, emphasizing personal ethics and the importance of inner tranquility.

Conversely, Epicureanism, founded by Epicurus, centered on the pursuit of pleasure, but advocated for a subtler understanding—pleasure was best achieved through moderation and the cultivation of friendships. Both schools of thought provided frameworks for understanding human existence outside the rigid structures of earlier philosophical schools.

B. Skepticism and the Search for Certainty

Hellenistic thought also included skepticism, with philosophers like Pyrrho questioning the possibility of certain knowledge. Skeptics emphasized the limitations of human perception and advocated for a suspended judgment. This approach highlighted the subjective nature of truth, prompting deeper inquiries into the essence of knowledge and belief, which would resonate through the ages.

III. The Middle Ages: Synthesis of Faith and Reason

A. Christian Philosophy

The advent of Christianity brought a new dimension to philosophical inquiries. Philosophers such as Augustine of Hippo integrated Platonic ideals with Christian theology, positing that ultimate truth is found in God. Augustine emphasized the significance of divine revelation and the soul’s journey towards understanding. His works prompted discussions on free will, ethics, and the relationship between faith and reason.

B. Scholasticism

The later Middle Ages saw the rise of Scholasticism, where philosophers like Thomas Aquinas sought to reconcile faith with reason. Aquinas employed Aristotelian thought to articulate Christian doctrines, arguing that reason and revelation are not contradictory but complementary. His “Five Ways” to demonstrate the existence of God highlighted the importance of rational inquiry within a theistic framework.

IV. The Renaissance and the Rise of Humanism

A. Humanistic Philosophy

The Renaissance (14th-17th centuries) prompted a rebirth of classical learning and a renewed focus on human experience and rationality. Philosophers such as Erasmus and Petrarch advanced humanism, emphasizing the value of individual dignity and the pursuit of knowledge. This period marked a shift in philosophical meaning, as thinkers began to prioritize secular subjects and human affairs alongside theological inquiries.

B. Descartes and the Foundation of Modern Philosophy

René Descartes (1596-1650) is often dubbed the father of modern philosophy. His famous dictum, “Cogito, ergo sum” (“I think, therefore I am”), underscored the significance of doubt and inquiry. Descartes sought to establish a firm foundation for knowledge through rationalism, emphasizing the role of reason in understanding existence. His methodological skepticism laid the groundwork for subsequent epistemological discussions, influencing thinkers like Kant and Hume.

V. The Enlightenment and the Quest for Knowledge

A. Empiricism and Rationalism

The Enlightenment (17th-19th centuries) represented a flourishing of philosophical thought, characterized by a strong emphasis on reason, science, and individual rights. Philosophers such as John Locke, George Berkeley, and David Hume advanced empiricism, asserting that knowledge arises from sensory experience. Locke’s tabula rasa theory posited that individuals are born as blank slates, shaped by their experiences.

In contrast, rationalists like Baruch Spinoza and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz argued that certain truths exist independently of experience. The tension between empiricism and rationalism became a central theme in philosophical discourse.

B. Political Philosophy

The Enlightenment also witnessed significant developments in political philosophy. Thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau explored concepts of social contract theory, individual rights, and governance. Their ideas prompted a reevaluation of authority and the role of the individual in society, paving the way for modern democratic principles.

VI. The 19th Century: Existentialism and the Challenge to Traditional Meaning

A. Hegelian Dialectics

The 19th century introduced new currents in philosophy, particularly through the work of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Hegel’s dialectical method—which posited development through the synthesis of contradictions—emphasized the dynamic nature of reality. His philosophy focused on the unfolding of Spirit (Geist) through history, suggesting that meaning is derived from the progression of human consciousness.

B. Existentialism

In response to Hegelian idealism, existentialism emerged, foregrounding individual existence, freedom, and choice. Thinkers like Søren Kierkegaard and Friedrich Nietzsche questioned established moral values, emphasizing the subjective nature of meaning. Kierkegaard’s notion of the “leap of faith” juxtaposed rationality with personal belief, while Nietzsche declared the “death of God,” challenging traditional sources of meaning and morality. His concept of the Übermensch advocated for individuals to create their own values and meanings.

VII. The 20th Century: Structuralism, Post-Structuralism, and Beyond

A. The Linguistic Turn

The 20th century saw a significant shift in the understanding of meaning through the linguistic turn, which posited that language shapes thought. Philosophers such as Ludwig Wittgenstein explored the relationship between language and reality, asserting that meaning is context-dependent and rooted in use. His later work emphasized the idea that philosophical problems arise from misunderstandings of language.

B. Structuralism and Post-Structuralism

Structuralism, championed by thinkers like Ferdinand de Saussure and Claude Lévi-Strauss, sought to uncover the underlying structures that shape human culture and thought. This perspective emphasized the relational nature of meaning, leading to post-structuralist critiques by figures like Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida. They challenged the notion of fixed meanings and objective truths, asserting that meaning is fluid and shaped by power dynamics and cultural contexts.

VIII. Contemporary Philosophy: Global Perspectives and New Frontiers

A. Analytical and Continental Philosophy

Today, philosophy encompasses diverse approaches, often divided into analytical and continental traditions. Analytical philosophy, represented by philosophers like Bertrand Russell and W.V.O. Quine, prioritizes clarity, logic, and the use of formal methods to analyze language and concepts. In contrast, continental philosophy explores broader human experience, drawing on existentialism, phenomenology, and critical theory.

B. Global Philosophical Contributions

Contemporary philosophy also reflects global perspectives, integrating insights from Eastern traditions, Indigenous philosophies, and feminist thought. Figures like Martha Nussbaum and bell hooks emphasize the need for intersectionality and ethics in philosophical investigations, challenging traditional Western narratives. The focus on plurality has enriched philosophical discourse, encouraging dialogues across cultures and disciplines.

IX. Conclusion: The Ongoing Evolution of Meaning in Philosophy

The evolution of meaning in philosophy from Ancient Greece to today encapsulates a journey marked by profound insights and transformative shifts. Each era and philosophical movement has contributed to a richer understanding of existence, knowledge, and ethics. As we navigate contemporary challenges and uncertainties, the legacy of philosophical inquiry remains vital—inviting us to this day to critically examine our beliefs, question the nature of truth, and explore the intricacies of human experience.

This journey reflects the enduring quest for meaning, a hallmark of what it means to be human, reminding us that philosophy is not merely an academic discipline but a lifelong endeavor, echoing Socrates’s call for self-examination and wisdom in the complexities of modern life.

References

- Plato. The Republic. Translated by Benjamin Jowett, Oxford University Press, 1888.

- Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by W. D. Ross, Oxford University Press, 1908.

- Augustine of Hippo. Confessions. Translated by Henry Chadwick, Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Aquinas, Thomas. Summa Theologica. Translated by Fathers of the English Dominican Province, Benziger Bros, 1947.

- Descartes, René. Meditations on First Philosophy. Translated by John Cottingham, Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich. Phenomenology of Spirit. Translated by A. V. Miller, Oxford University Press, 1977.

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Translated by R. J. Hollingdale, Penguin Classics, 1961.

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Philosophical Investigations. Translated by G. E. M. Anscombe, Basil Blackwell, 1953.

- Derrida, Jacques. Writing and Difference. Translated by Alan Bass, University of Chicago Press, 1978.

- Nussbaum, Martha. The Fragility of Goodness: Luck and Ethics in Greek Tragedy and Philosophy. Cambridge University Press, 1986.

- hooks, bell. Feminism Is for Everybody: Passionate Politics. South End Press, 2000.

This framework provides a structured overview of the evolution of meaning in philosophy over time, incorporating key philosophical ideas, figures, and developments. If you need any specific sections expanded or adjusted, feel free to ask!

Add Comment