Heartbeat: Understanding the Mechanics of Circulation

Introduction

The heartbeat is an intricate yet vital component of human physiology, underpinning the circulatory system’s ability to transport oxygen, nutrients, and waste products. As we delve into the mechanics of circulation, we will explore the heart’s structure, function, and the physiological mechanisms that sustain life through blood circulation.

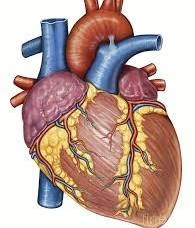

Anatomy of the Heart

Structure

The heart is a muscular organ roughly the size of a fist, located slightly left of the center of the chest. It consists of four chambers:

- Right Atrium: Receives deoxygenated blood from the body via the superior and inferior vena cavae.

- Right Ventricle: Pumps the deoxygenated blood to the lungs through the pulmonary arteries.

- Left Atrium: Receives oxygenated blood from the lungs via the pulmonary veins.

- Left Ventricle: The strongest chamber, responsible for pumping oxygenated blood to the entire body through the aorta.

Valves

Four key valves ensure unidirectional blood flow through the heart:

- Tricuspid Valve: Between the right atrium and right ventricle.

- Pulmonary Valve: Between the right ventricle and pulmonary artery.

- Mitral Valve: Between the left atrium and left ventricle.

- Aortic Valve: Between the left ventricle and aorta.

These valves operate via a series of pressure differentials that open and close them during the cardiac cycle, preventing backflow and ensuring efficient circulation.

The Cardiac Cycle

The cardiac cycle is divided into two primary phases: diastole and systole.

Diastole

During diastole, the heart muscles relax, allowing the chambers to fill with blood. This phase can be subdivided into:

- Isovolumetric Relaxation: The heart’s chambers are filling with blood, but all valves are closed.

- Rapid Filling Phase: The atrial pressure exceeds ventricular pressure, causing the atrioventricular (AV) valves to open, and blood flows from the atria to the ventricles.

- Atrial Systole: The atria contract, pushing additional blood into the ventricles, completing their filling.

Systole

Systole occurs when the heart contracts, pumping blood out of the chambers:

- Isovolumetric Contraction: The ventricles contract with all valves closed, increasing pressure within the ventricles.

- Ventricular Ejection: Once ventricular pressure exceeds arterial pressure, the aortic and pulmonary valves open, allowing blood to be ejected into the aorta and pulmonary artery, respectively.

- End of Systole: The ventricle relaxes, and pressure drops, leading back into diastole.

The entire cycle typically lasts about 0.8 seconds in a resting adult, resulting in an average heart rate of 60-100 beats per minute.

Electrical Conduction System

The heartbeat is regulated by an intrinsic electrical conduction system that coordinates muscle contractions. Key components include:

Sinoatrial (SA) Node

Often referred to as the heart’s natural pacemaker, the SA node initiates electrical impulses that lead to heart contraction. It is located in the right atrium and has the highest rhythm-generating ability.

Atrioventricular (AV) Node

After the SA node generates an impulse, it travels to the AV node, which serves as a gateway to the ventricles. It briefly delays the signal, ensuring the atria have sufficient time to contract and fill the ventricles.

Bundle of His and Purkinje Fibers

The electrical impulse then travels down the Bundle of His and into the right and left bundle branches, branching into the Purkinje fibers. This network facilitates coordinated contraction of the ventricles, pumping blood effectively.

Hemodynamics: The Physics of Blood Flow

Blood Vessels

The circulatory system is comprised of three types of blood vessels:

- Arteries: Carry oxygenated blood away from the heart (except for the pulmonary arteries).

- Veins: Return deoxygenated blood to the heart (except for pulmonary veins).

- Capillaries: Microscopic vessels where gas and nutrient exchange occurs between blood and tissues.

Blood Pressure

Blood pressure is defined by two measurements: systolic and diastolic pressures. It is essential for maintaining adequate blood flow throughout the circulatory system:

- Systolic Pressure: The force exerted by blood against artery walls during ventricular contraction.

- Diastolic Pressure: The pressure in the arteries when the heart is at rest between beats.

Cardiac Output

Cardiac output (CO) is the volume of blood pumped by the heart per minute. It is calculated using the formula:

[ \text{Cardiac Output (CO)} = \text{Heart Rate (HR)} \times \text{Stroke Volume (SV)} ]where stroke volume is the amount of blood pumped by the left ventricle in one contraction. The average cardiac output is approximately 4 to 8 liters per minute in adults.

Regulation of Heart Rate

Heart rate is influenced by various factors:

Autonomic Nervous System

The autonomic nervous system consists of sympathetic and parasympathetic branches that modulate heart rate:

- Sympathetic Nervous System: Increases heart rate and contractility during stress or exercise through the release of norepinephrine.

- Parasympathetic Nervous System: Decreases heart rate during rest via the vagus nerve, which releases acetylcholine.

Hormonal Influences

Hormones such as adrenaline (epinephrine) and cortisol can also impact heart rate, especially during stressful situations or exercise.

Pathophysiology of the Heart

Common Heart Conditions

The heart is susceptible to a range of conditions, including:

- Coronary Artery Disease (CAD): Narrowing of the coronary arteries, leading to reduced blood supply to the heart muscle.

- Heart Failure: The heart’s inability to pump effectively, often due to previous heart attacks or high blood pressure.

- Arrhythmias: Abnormal heart rhythms that can disrupt effective blood circulation.

- Valve Disorders: Malfunction or stenosis of heart valves, affecting blood flow.

The Role of Lifestyle in Cardiac Health

Diet and Nutrition

Heart-healthy diets rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats can significantly reduce the risk of cardiovascular diseases. Conversely, high saturated fat, sugar, and salt intake can increase the risk of heart disease.

Physical Activity

Regular exercise strengthens the heart muscle and improves circulation. Aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity or 75 minutes of vigorous activity weekly.

Stress Management

Chronic stress can negatively impact heart health, leading to elevated blood pressure and increased heart rate. Techniques such as mindfulness, yoga, and relaxation exercises can help mitigate stress.

Regular Health Check-ups

Routine monitoring of blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and overall cardiovascular health can help in early detection and prevention of heart disease.

Conclusion

Understanding the mechanics of circulation and the importance of a healthy heart is vital for maintaining overall well-being. By appreciating the complexities of the heartbeat and the circulatory system, individuals can make informed choices about their health, leading to a longer and healthier life. Regular check-ups, a balanced lifestyle, and awareness of cardiovascular health can help in the prevention of various heart conditions.

Through education and proactive health management, we can nurture our hearts, ensuring they continue to pump life-sustaining blood for years to come.

While this article captures the essence of the mechanics of circulation and heart health, further research and tailored advice from healthcare professionals are always recommended for individual circumstances.

Add Comment